A Short Essay On Our Existence

Glimpse into a clear night sky, we all once questioned

Are we alone?

Some categorically assert we are alone, others embrace in their secretive the wildest conspiracy theories. Given everything in the universe is matter and energy, both suppositions are inconclusive: the former is guilty of anthropocentrism, the latter is paranoid.

In order to debunk the question, Frank Drake raised these questions:

-

How many stars in our galaxy?

-

How many of these stars have planets around them?

-

How many of these planets can bear life, like water and suitable temperature?

-

How many of these planets eventually beared life?

-

How many of these life forms have evolved into intelligent beings (and consequently, civilizations)?

-

How many of these intelligent civilizations can communicate with signals that we can detect?

-

How long do these civilizations send signals to space?

Trivia: A typical galaxy like ours bears around the same number of stars as the number of neurons in a human brain.

In a simple way, a star, such as our Sun, is a shiny, huge, hot gas ball, while a planet is a vast body that revolves around a star. When a solar system is born, planets emerge as subproducts of stars with the remaining material from stellar formation. Over tens of millions of translational motions, this matter joins together by mutual attraction until it has critical mass to form a planet by accretion.

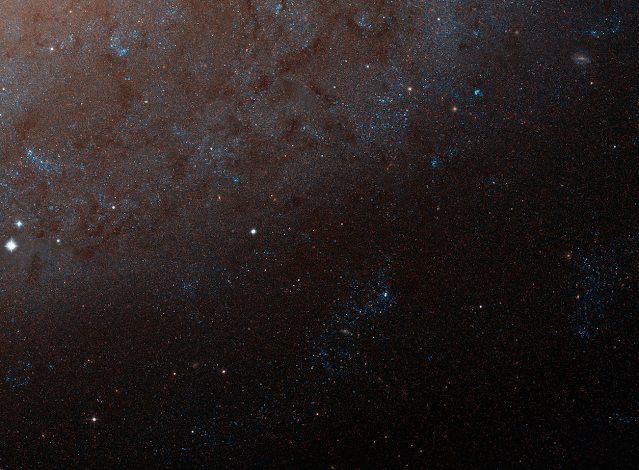

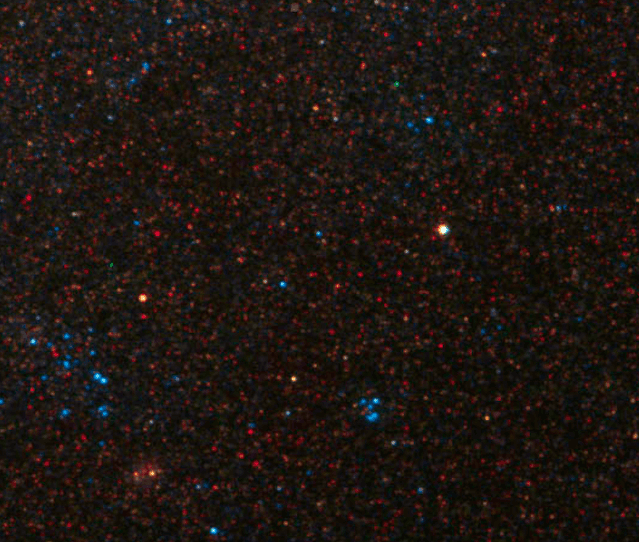

As an example, in the photo above, we are zooming into the periphery to elicit dimension. Every bright dot displays a stark, bright star.

There are more stars than initially appear, though, camera can only capture the shinest ones. Despite this ludicrous resolution, we captured less than 1% of 1% of the stars of Bode, there are around 10 million in the photo against 250 billion that really exist.

Stars are apparently quite close to each other as close as neighbours, in reality they are far apart. Photo capture emitted light, not the stars themselves, which are much, much smaller, so small they wouldn't even appear. If each star were a ball, they would be as far apart as Milan and Munich.

Back home, eight planets now make up the solar system, with Pluto being demoted to the honourable category of dwarf planet, along with Eris, Ceres, Haumea, and Makemake. We express their distances to the Sun in astronomical units (AU), which is the average distance between the Sun and the Earth (≈150 million km).

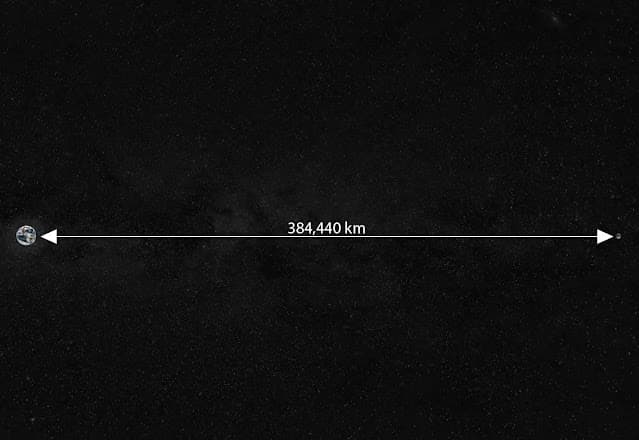

One might struggle with magnitudes. Science classes tell us that the planets are equidistant orbiting a huge yellow ball a bit bigger than Jupiter. Put to scale, planets are minuscule and incredibly distant from each other they would be hardly spotted with unaided eye.

Below is a realistic representation of the Earth and the Moon for scale.

When closer to Earth, Venus is "only" a hundred times this distance. Picture a hundred screens of your phone/laptop side by side for a better sense.

This video displays the Sun and planets in scale. On the other hand, this other site displays a precise scaled model of the solar system.

Distances between local planets seem to follow two progressions, first until Mars, then Jupiter and beyond. In between Mars and Jupiter something curious happens. Suddenly, the distance increases much more than expected, as if there had to be a planet to fulfil the pattern. Should there be a planet? Could it eventually bear life?

Not all planets provide the necessary means to bear life as we know. Among local neighbours none has liquid water on the surface. The larger ones don't even have a flat surface, Jupiter to Uranus are essentially gas giants in motion.

To be eligible to host life, a planet must be rocky enough to have a solid surface and must orbit a star at a reasonable distance: not too close, not too far. This special region is called the Habitable Zone (HZ), only there a planet's surface can accommodate liquid water in abundance, essential for life. Contrary to popular belief, water is common in the universe and here's why: covalent bond between hydrogen and oxygen, two of the most abundant atoms in the universe. Comets and asteroids contain ice water; star clouds contain water vapour; the jovian moon Europa and the saturnian moon Encelado have huge underground oceans.

As Earth stands at 1.00 AU, the habitable zone extends roughly from 0.95 AU to 1.37 AU, that is, a bit closer to the Sun and a few steps further away. Note neighbours Venus and Mars are outside this zone.

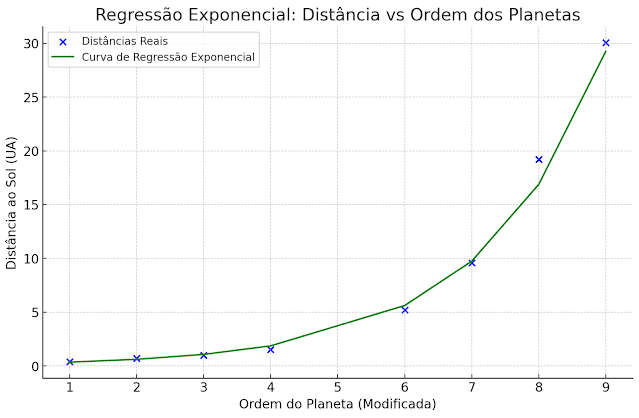

Below is an approximation I devised. From one planet to the next, distance increases by around 73% given

This is the estimated distance for the planets

| Planetary order (PO) | Planet | Distance (AU) | Estimated distance (d) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Mercury | 0.39 | 0.36 |

| 2nd | Venus | 0.72 | 0.62 |

| 3rd | Earth | 1.00 | 1.08 |

| 4th | Mars | 1.52 | 1.87 |

| 5th | No planet (asteroid belt) | – | 3.24 |

| 6th | Jupiter | 5.20 | 5.62 |

| 7th | Saturn | 9.58 | 9.84 |

| 8th | Uranus | 19.22 | 16.92 |

| 9th | Neptune | 30.05 | 29.12 |

and this is the graphical representation of the estimated distance as a function of the planetary order

Had Jupiter been less of a glutton, attracting less matter in its formation process, a new planet could have formed where the asteroid belt stands, approximately 3.24 AU, outside the habitable zone. If it were smaller, Jupiter would have a weaker gravitational influence on Mars, which would bring this last one a bit closer to the Earth, perhaps even within the habitable zone. But that's not the case.

Because planets are formed from the remains of stars, it is reasonable to assume that the larger the star, the more remains there will be and the greater the chance of finding a rocky planet in the habitable zone.

With proper conditions life can emerge. But first let's define what life is. A living being is a stable organism, capable of reacting to its environment, making chemical reactions to use energy, reproducing to generate descendants, and adapting to the environment at a species level; in technical terms, it reacts to stimuli, metabolises, maintains homeostasis, reproduces, and its species evolves. The universe may admit other forms of life, perhaps with a distinct genetic material and a quirk metabolism, after all, the imaginative exercise is left for the reader.

Water on Earth dates back almost to the terraformation, 4.5 billion years ago, albeit life only emerged more than a billion years later.

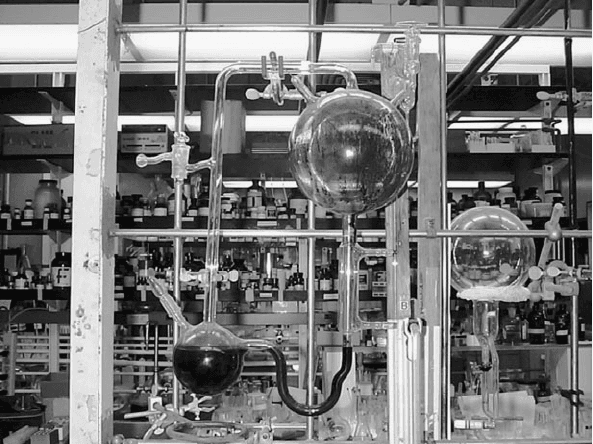

Oparin hypothesised that life would have emerged spontaneously from inorganic matter. Then Stanley Miller, under the supervision of Nobel laureate Professor Urey, conducted an experiment simulating Earth's atmospheric conditions before the advent of life.

Running experiment was simple: in a closed system of glass tubes, using a mixture of gases (methane, ammonia, hydrogen and water vapour) and applying electrical discharges to mimic lightning, also alluding to ultraviolet radiation and volcanic activity, after a few days, amino acids emerged, demonstrating that essential organic molecules could have formed naturally in pre-biotic environments. Amino acids are fundamental building blocks of proteins and appear in the genetic code of all living beings. Through transcription of the genetic code base sequences organisms are replicated and life is continued.

One might consider discussing the coacervates, a notion also put forth by Oparin in a supplementary manner, proposing that life could have emerged from minuscule droplets of organic molecules suspended in solution (coacervates). These droplets form spontaneously when mixtures of proteins, lipids, and various other compounds cluster together, therefore establishing a separation between the external and internal environments, somewhat resembling a membrane. Coacervates are regarded as proto-cells, sitting at an intermediate stage, a bridge between rudimentary organic molecules and the earliest true cells as in living organisms, despite their inability to reproduce or metabolise.

The first living beings were simple, unicellular (known as prokaryotes), like bacteria and archaea (which share many similarities with bacteria). It is highly likely that the first step towards complex life began when an archaea engulfed and assimilated a bacterium. This symbiotic event gave rise to what is believed to be the first eukaryotic organism, the precursor to all plant, animal, and fungi cells.

The engulfed bacterium quite likely performed the function of a mitochondrion, specialised in a process that breaks down glucose to generate energy and releases oxygen as a by-product. The archaea, in turn, provided protection and nourishment to the bacterium. This cooperation gave rise to a more complex and energetic being, fostering the evolution of larger and more diverse organisms. The proliferation of these beings, in the process we call photosynthesis, over hundreds of millions of years, changed the entire atmosphere composition, filling with oxygen.

Next up, multicellular beings emerged, where cells are specialised and work in cooperation, such as sponges, algae, corals, and jellyfish. With specialised cells, multicellularity allowed the evolution of organs and tissues to form more complex individuals, as observed in modern animals, plants, and fungi.

One must notice the subtle interplay between collaboration and competition permeating distinct scales of nature. Cells unite synergically, extending to animals cooperating in the hunt for food and territory.

The earliest life forms reproduced in quite simple ways without requiring a partner. Bacteria divided in two, fungi formed spores capable of developing into new organisms, and yeasts and corals reproduced through budding.

With each generation, the new individual inherits predominantly characteristics from its parent(s) and possibly emerges with unique characteristics, called mutations, allowing these beings to be more or less suited to their environment. The most successful ones, those that manage to reproduce, are said to be selected. Thus, these characteristics are passed on. This optimization that occurs across generations is the evolution of the species.

Over time, beings of the same species may become separated by natural barriers or behavioral changes. Each group adapts to its environment and accumulates small differences through mutation and selection. After many generations, these differences can become so significant at the species level that they can no longer reproduce with each other, and this is how new species emerge.

In the Cambrian explosion, half a billion years ago, a family of more complex beings emerged, such as arthropods, mollusks, and chordates, all with some rudimentary nervous system. Subsequently, the first vertebrates appeared, likely an evolution of the chordates.

In this evolutionary panorama, some transitioned to land, where fish fins specialised to the point of becoming limbs, allowing these animals to operate both in water and on land, hence the first amphibians. Those that specialised on land, with resistant skin and hard-shelled eggs, opened a new niche —the first reptiles.

These first reptiles divided into two major groups: the synapsids (ancestors of mammals) and the sauropsids (ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, and modern reptiles). Rather fascinating, what unites most mammals, besides the obvious traits, are the seven vertebrae in the neck: humans, whales, rats, lions, horses, bats, and —would you believe it— giraffes; indeed, we have the same number of neck vertebrae as giraffes.

These first beings were rather small; it wasn't until later that animals of colossal dimensions emerged. In fact, there's a direct relationship between the size and mass of animals and the distribution of oxygen in the atmosphere - 30% back then compared to today's 21%. Due to this and other minor factors, one doesn't see terrestrial animals of dimensions like the Argentinosaurus, which was 30 metres in length and weighed 70 tonnes.

There are currently over 8 million living species, including animals, plants, fungi, protists, and bacteria. This is only a tiny fraction of all species that have ever existed. Estimates suggest there may have been as many as 1 to 4 billion species historically.

With a bit of imaginative gymnastics, all living beings descend from a common ancestor. It's easy to see the similarities between humans and hominids, and we can form successively larger groups: primates, mammals, chordates, other animals, and finally, complex multicellular beings.

Among all extinct species to contemporary ones, among the many kingdoms of nature, in this great tree that connects the traces of precursor species to current ones, there must have been around 30 levels of bifurcations linking all species back to the first eukaryote, that aforementionedarchaeon that engulfed the bacterium.

One of the negative effects of anthropocentrism is the rather distorted notion that only humans think and other animals are mere supporting characters in the nature. In fact, there are few species that have supreme consciousness, at least where individuals are capable of perceiving themselves and their surroundings.

I shall list some notable cases worthy of attention.

-

Mammals: Elephants, dolphins, and pigs possess various advanced cognitive capabilities, such as long-term memory (particularly elephants, with triple the neurons of humans), ability to plan and solve problems and puzzles, social learning, use of tools to facilitate tasks, all demonstrating self-awareness by passing the mirror self-recognition test, complex behaviours and sophisticated forms of communication. Dogs, cats, and some primates, albeit in a much more limited fashion, also make the tail end of this list.

-

Birds: Crows can plan complex tasks. Parrots can learn through imitation, typically managing to learn between 30 and 200 words.

-

Fish: Clownfish demonstrate complex social behaviour and some level of rudimentary self-awareness.

-

Insects: Bees and ants exhibit collective behaviour and decision-making at a basic level of perception, although part of their behaviour is dictated by chemical-olfactory stimuli.

-

Cephalopods: Octopuses demonstrate complex problem-solving abilities, good memory and observational learning, distinct and individualised personality, sophisticated social behaviour; in captivity, they can open jars, solve mazes, escape aquariums, use tools, elaborate ambushes and hunting tactics, deceive predators, and manipulate through tactical mimicry. Rather splendid!

Animal intelligence extends across a broad tapestry, from sponges, sea cucumbers, and jellyfish to bonobos, dolphins, elephants, and octopuses. On the other hand, what characterises homo sapiens' rationality is our unparalleled level of deep abstract reasoning and systematic planning.

With complex communication, critical thinking, logical reasoning, creativity, cooperation, long-term planning, and cumulative culture, we have managed to rise above the food chain, create civilisations, and unravel the sciences to a level of space communication.

In retrospect, this is where the largest gap lies.

Among the more than one billion species that have ever existed, among the sextillions of beings of all species that have ever lived, among the more than one hundred billion people who have lived or are living, only a very limited number of human beings have culturally contributed to developing the sciences to the point of transmitting the first message to the confines of the galaxy.

If our hundreds of thousands of years of existence as a species were expressed in 24 hours, this transmission would have happened 14 seconds ago, considering that 30 seconds ago we wouldn't even have had the technology to make such transmission, and in the same timespan, we have developed technology to destroy our civilisation at the stretch of an arm.

Upon introspection, a species does not exist forever, and civilisations are far more ethereal.

These last paragraphs deserve a moment of reflection.

We exist on a solitary rock,

Scarce among the self-aware,

Rarest amongst the astro-communicative,

A spark in the darkness, pulsing for a fleeting moment.

As pathetic as it may seem, it's a brief poetic reading of our existence.

The Neanderthals, extinct in the Pleistocene, lived for roughly the same time as sapiens. The erectus, who mastered fire and rudimentary tools, about two million years. Other pithecines, like the infamous Lucy, roughly the same time window. Prior to hominids, the first primates emerged shortly after the dinosaurs' extinction. Even more remote, we have the first mammals in the Triassic.

Of all hominids, we're the only species that hasn't gone extinct, though we've had several close calls:

-

Mass extinction of dinosaurs. Before hominids, still in the Cretaceous, the most accepted theory is that a gigantic asteroid impact in what is now the Yucatan Peninsula was powerful enough to cause profound climatic changes that led to the mass extinction of most dinosaurs.

-

Cuban Missile Crisis. At the first launch of an atomic weapon, the situation could have globally escalated within minutes to multiple attack targets with global involvement until total destruction. Both poles had submarines with nuclear warheads in undetectable positions to ensure mutual destruction —that is, if one country destroyed the other, the first would surely also be destroyed by these submarines— which remain operative to date. Ukraine's potential NATO membership, another story with the same plot, represents an existential risk for Russia, and the response might ultimately involve nuclear weapons and the scenario could escalate beyond control.

-

Historical Pandemics. The bubonic plague, which on two occasions took the toll of half the Mediterranean population, the Spanish flu in similar proportions, smallpox for having killed 90% of the indigenous population in the Americas. Although no pandemic has been capable of ending human life, it may be a matter of time before finding just one apocalyptic configuration: means of transmission, virality (r factor), incubation window, lethality, detectability, resistance, and pathogen mutations rendering vaccines ineffective.

-

Mount Toba Eruption on Sumatra island in Indonesia 74,000 years ago reduced the human population to something like one to ten thousand individuals. Since humans lived in groups of 20 to 50 individuals, there were as few as 30 to 40 groups from which we all descend. There are so few individuals that this genetic bottleneck explains the low human genetic diversity, so much so that the most distinct individuals are grouped by ethnicities rather than races!

-

Encounters with other hominids. Given that sapiens coexisted with other hominids, especially Neanderthals and Denisovans, conflicts and competition for resources may have led these hominids to extinction instead of us.

-

Extinction of Cro-Magnons. The most accepted theory is that sapiens exterminated the Cro-Magnons, but there are other theories suggesting that Cro-Magnons exterminated most sapiens.

Finally, combining all these factors, of all the stars in our galaxy, we look again at Drake's formula, mentioned in the first paragraphs. The most conservative estimate gives a total of 20 civilisations, and the super-optimistic one shoots beyond thousands of intelligent civilisations in the Milky Way.

Rather mad, isn't it! Well, these are the official estimates. In my estimates, I took a conservative approach with a range of 0.03 (meaning none) to 30 civilisations.

For the time span it would take us to send a hello to the diametrically opposite side of the galaxy's tentacles, we'll likely become extinct long before, whether through nuclear or biological weapons, pandemics, misuse of artificial intelligence, or climate change. This fatalistic view isn't necessarily deterministic; after all, our certainties are enumerable.

Even though these probabilities are small, they accumulate and become substantial threats in the long term. Let's reverse the logic to enlighten more sceptical minds. For example, if every year the probability of a nuclear holocaust occurring is 1%, it's practically certain that this scenario won't materialise the following year; however, in 50 years the narrative changes, the a priori probability rises to 40%. Imagine in 200 years, optimistically the chance of emerging unscathed is 1 in 7.

Turns out some risks are brand new. Nuclear weapons have existed for less than a hundred years, which is nothing compared to the 12,000 years since we sedentarised or the 300,000 years we exist as a species. Changes in climate vectors, slow and difficult to reverse, will also take its toll within a few generations. The dystopia of an increasingly unnatural society is also a freshly-unveiled risk that's gaining strength as we build the scaffolding of modern society.

We're victims of our own nature that bends the correct notion of risk. Linear thinking, herd behaviour, and belief in magic dykes, such as "this pandemic will never reach 1 million people" followed by "this pandemic will never reach 100 million people," "country XYZ will never dare strike with nuclear weapons" or the dystopian "my appliances won't turn against me." What I mean is that these barriers aren't absolute, and from time to time, human ignorance meets reality checks.

While we exist, perhaps we could leave our mark on the universe, innit? Tell whatever living beings out there that we existed, that we achieved things, that we almost got there.

Although the existence of some intelligent civilisation far from here is admissible, we just face a lack of evidence. We've had radio receivers listening to space for over 40 years and have never received any relevant signal. Among billions of planets out there, right here nearby, we have no evidence of company. In other words, where is everyone? Life should be extremely common in the universe, but what we see is the opposite.

Are there other reasonably intelligent life forms that, for some reason, couldn't develop to the point of galactic communication and couldn't survive?

An intelligent civilisation would hardly dare establish interstellar contact; common sense says it's better to be alone than in bad company. War protocols and game theory agree. So, back to the first paragraph, for what purpose compose a message and send it into outer space?

In any case, if we ever find life in the galaxy, this will be the worst news humanity has ever received. Further context ahead.

Finding life in the galaxy would indicate that life is something common in the universe, suggesting that the absence of signs of advanced civilisations like ours might be the result of catastrophic factors, such as self-destruction or inevitable natural events, implying our future is threatened. In this train of thought, if we really find intelligent life or even complex microbial life, this suggests that the necessary steps for the emergence of technological civilisations aren't so rare. This leads us to the disturbing possibility that something prevents civilisations from advancing and surviving for long periods. We call this barrier the Great Filter.

The Great Filter could be in the past or in the future, meaning we've either already passed it or it's yet to come.

-

If it's in the past, it means we've already overcome the most critical phase and we are the exception. In such case, the great filter might have been abiogenesis (the emergence of life from chemical reactions), atmosphere development, transition to more complex cells (eukaryotic), emergence of multicellular organisms, development of sensory organs, intelligence, tooling development, transmission of accumulated culture, engineering involved in creating a radio transmitter, survival of catastrophic events, and even other more banal events by serendipity.

-

If it's in the future, it implies all civilisations eventually encounter an inevitable obstacle, such as environmental collapse, nuclear self-annihilation before interplanetary colonisation, cosmic catastrophes, or various fates that prevent them from becoming communicative civilisations, incapable of colonising other planets and traveling between solar systems.

Thus, finding life indicates that the emergence of life isn't the filter per se, increasing the chances that something more atrocious, still ahead of us, might be the reason why we don't see other civilisations flourishing in the galaxy.

It may be that our scientific knowledge and technological engineering prowess exceed our wisdom and our capacity for collective management in the geopolitical field. Perhaps, whenever a civilisation instrumentalises a means of self-destruction, the countdown begins and its fate is sealed by the fragility of a trigger.

Be mindful our entire discussion is about our galaxy, but there is an immeasurable profusion of other galaxies. In the observable universe, we can see two trillion galaxies, each with tens of billions to trillions of stars, many of them populated with planets in conditions similar to ours. To give dimension of what two trillion looks like, it corresponds to the number of sand grains in ten full trucks or the number of green ash leaves in a space filled with trees in six New Yorks. This is just what we can see, wherefrom light has reached, not what really exists, wherefrom light hasn't yet arrived here.

This visible horizon of universe, which we call the observable universe, is homogeneous and isotropic, meaning it's equally dense in galaxies in all regions and it looks the same in all directions we see. From what we see, everything indicates that it's much larger, with many more galaxies. Not a tale, this is the most direct reading made from probes and telescopes, all this is real and fits well in our scientific-cultural mosaic.

By no means do I intend to proselytise my few readers, dissuading from a pantheistic or agnostic view, nor persuade to a mild version of cosmic religiosity. I quote Einstein without compromise:

There are two ways of living life: one is as if nothing is a miracle;

the other is as if everything is a miracle.